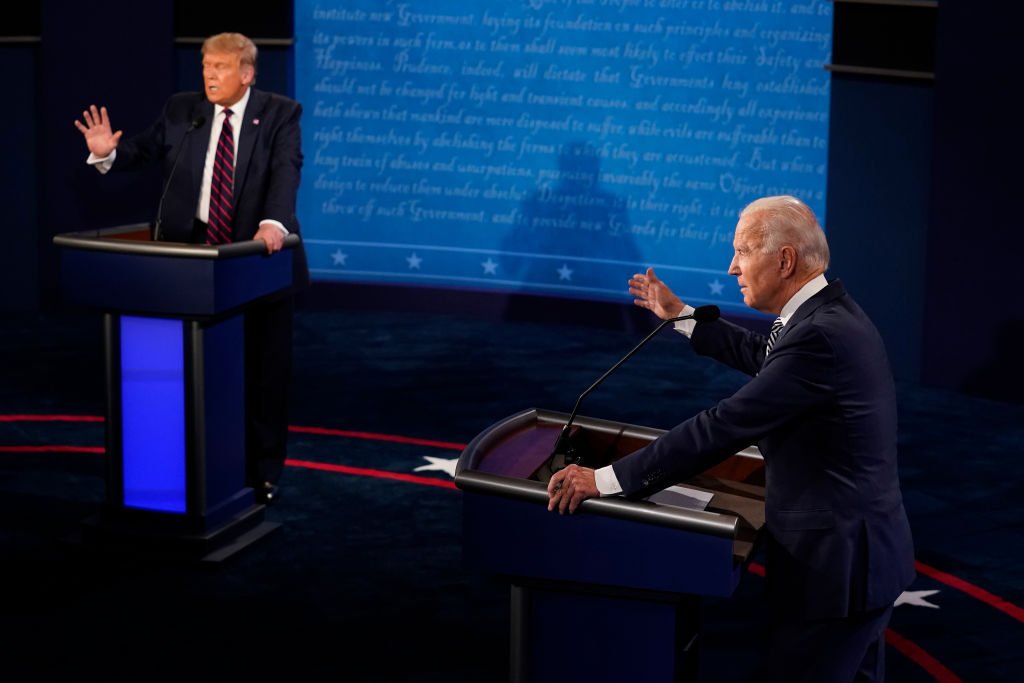

It’s not often that we find ourselves at a pivotal moment in history. With the US presidential election bearing down on us we stand at a crossroads, the like of which America has not seen before. The election will become either a footnote in politics or a milestone in a potentially sinister political journey that will eventually touch us all.

Over the last five months, Working Voices has been digging into the election in detail. I wanted to draw from it examples of what happens when norms in leadership and communication come to be challenged. This is a fear shared by those of us concerned about white supremacy, climate change, QAnon, truth and democracy.

These issues raise questions about trust and understanding. Ultimately, they come down to the question of how truth is being treated in the world’s biggest communications battle. In my search for answers, I’ve been talking to leading historians, political scientists and psychologists. I’ve discovered some worrying trends and conclusions, and I explore these in depth in a series of four short films.

Trusting to truth

Within parts of the Republican and Democrat campaigns, truth is fraying at the seams. All too often, its fine nuances are torn apart and then stitched up by crude fabrications woven together from biases and binary thinking. As individuals, we can uphold our own perceptions of truth and integrity, but we could use a little support from the top.

So what’s going on at the top? How has the election campaign been fought? And what has become of trust, truth and honesty along the way?

Episode 1: Them and us

In previous decades, political parties were a small part of a wider American culture that was broadly shared by the population at large. Not any more. These days, many voters on both sides feel they ‘belong’ to a sub-culture – which is completely understood by their particular political party and completely rejected by the other. Alex Theodoridis, political scientist at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, told me that “party identity is now so tied in with all these other identities, our race, our education level, our social status, where we live, that it becomes just a visceral, deep part of who we are”.

To people who are fearful of economic and political change, a sense of belonging offers a safe feeling of refuge. But it brings risks. Psychotherapist Dr. Aaron Balick told me about problems stemming from flawed thinking, such as confirmation bias and filter bubbles where “we tend to discount information that contradicts ideas about the world.” Psychoanalyst Dr. Justin Frank explained the limitations of binary thinking – which is prevalent in social media and can easily spill into violence on the streets. Ultimately this is what ‘them and us’ can lead to, which is why I wanted to highlight the dangers of tribal behaviour in the first place.

Episode 2: Conspiracy theories

In our second episode, we explore the bizarre world of conspiracy theories, which are “an unnatural overextension of the tendency to want to understand what’s going on”, according to Sheldon Solomon, Social Psychology Professor at Skidmore College. For Aaron Balick, conspiracy theories are an element of magical thinking. They are dangerous because “when you believe in Santa Claus, you also believe in the monster under the bed” – which can lead to members of a group reinforcing their sense of identity by uniting in fear against imagined ‘monsters’.

Ruth Ben-Ghiat, historian at NYU and author of Strongmen, suggests the desire to find identity in this way can be easily exploited by politicians. According to Ben-Ghiat, this is why Donald Trump “rode the wave” of rumours about President Obama’s birth certificate. Solomon says some people believe “there’s a conspiracy to rig the upcoming election by fraudulent mail-in ballots, which is absurd.” While some among us may enjoy earnestly telling friends that the world is run by lizard people, I’ve discovered that those who engage in conspiracy theories are less likely to trust accurate sources. The threat here is the damaging impact on the shared sense of truth that we depend on in any organisation – from a small business to a country.

Episode 3: Reality as entertainment

Core values help any organisation, or hinder those who forget them. Along with clear thinking and a shared sense of truth, such values include the ability to make decisions. For over 20 years I’ve been helping clients develop skills in these areas, and I’ve found that decision-making relies on clearly knowing fact from fiction. However now that our powerful entertainment culture is subverting reality, there is a danger that we might ditch the truth in favour of idealistic, alternative non-‘realities’. We think we’re looking at the real world, but how can we make accurate decisions if we’re actually gazing at a construct dreamed up by clever producers – a case in point being The Apprentice.

Leadership psychologist Darryl Aiken-Afam fears that “the American intellect has been dumbed down”. This is no accident, according to psychotherapist Dr. John Gartner who explained the power that lies in manipulating facts: “Crooked Hillary. You know, she wasn’t crooked, but it stuck”. Ruth Ben-Ghiat fears that such manipulation is “key to the kind of media ties, politics and spectacle that we have today.” Abandoning the truth in favour of false promises is disastrous in any country, just as it is in a company in which the board sell themselves a mistaken version of reality – and then believe everything will be alright in the morning.

Episode 4: Misinformation

When we’re chatting in person, we can easily see whether information is to be taken seriously or dismissed as gossip. We can see the reaction of other people, for example when they laugh at something incredulous. When we communicate in person there is nuance and care – less so when we communicate virtually. Scrolling alone on a screen, we don’t see when gossip is dismissed by other people, it’s easier for misinformation to take root. This effect is exploited by those who deliberately deceive others through the creation of fake news and disinformation. According to Paul Barrett, law professor at NYU, in 2016 “you had Russian operatives assuming the identities of Americans falsely promoting information designed to push people in the direction of voting for Donald Trump.” Intelligence agencies believe this has been happening again in the 2020 campaign.

Nevertheless most misinformation in America originates from Americans, usually pushing a political agenda tinged with their own particular biases. Indeed, Barrett believes that “the leading purveyor of disinformation in the US sadly is our president.” Ultimately, confusion about the truth leads to apathy – which political scientist Rachel Bitecofer described to me as “the indifference problem”. In this atmosphere of disinterest and uncertainty, it’s easy to stop questioning things. Consequently, alternative realities are allowed to prevail. These often support a narrative of ‘them and us’ – which is pretty much where we started.

Shaking the ground we stand on

As the second wave of Covid begins to bite, more of us are working from home. Businesses struggling in unprecedented circumstances are dependent on individuals’ creativity, commitment and the ability to work alone. These skills rely on critical thinking and are effective only in an atmosphere of trust and honesty. How can someone working remotely believe they are valued if there is no shared perception of truth, no mutual sense of trust? The erosion of these values inevitably touches us all, particularly through social media.

Given the scale of the pandemic, these are unsettled times. Shaking the ground we stand on is hardly going to help. Of course, all elections culminate in a winner, eventually. My sincere hope is that truth, honesty, imagination and the freedom to champion diversity are not among the losers.